Arnold Mesches: A Life’s Work at Miami Dade College Museum of Art + Design and MDC’s Kendall, Wolfson, and North Campus Galleries reveal the life and times of the prolific artist and activist in an ambitious retrospective.

By Jill Thayer, Ph.D., Contributing Writer, ARTPULSE Magazine

MIAMI – During the Great Depression, artists portrayed the plight of the working class by exposing the dire economic and social conditions of the 1930s. Throughout this period, Arnold Mesches developed a penchant for social change. His left-wing proclivities and outspoken activism defied the social structures perpetuating these conditions, which informed his voice in Social Realism. Mesches’ figurative style evoked that of the gestural Action Painters, as his work would rival the critiques of genres to follow––the human existence in Existentialism; the instinctual understanding of Abstract Expressionism; the commodified culture represented by Pop Art; the literalness in Superrealism; the emotive intensity in Neo-Expressionism; and the transformative liberation in Feminism. His formal grounding set into motion a lifelong inquiry of art’s historical trajectories, which would transpire into contemporary culture. The paintings and drawings Mesches produced throughout his nearly seven-decade career expound upon issues of the day through a mise-en-scène of masterful articulation.

Arnold Mesches: A Life’s Work is presented in a retrospective at Miami Dade College Museum of Art + Design. The exhibition portrays the artist’s powerful and thought-provoking depictions of a changing society amidst turbulent times in our country’s 20th Century history. The horrors of WWII, the anti-communist crusades of the McCarthy Era, civil rights, the Vietnam War and peace movement, social stratification, the political policies of the Reagan and Bush years, terrorism, and the Iraqi War are a sampling of the cultural contexts Mesches defines.

The main gallery features more than 85 works from 1945-2012 including large paintings from many of the 14 series completed. Curated by Kim Levin, the exhibition marks Arnold Mesches’ 90th birthday and 136th solo show to date. A Life’s Work is augmented by three satellite campus galleries totaling over 200 works. An elaborately designed 280-page book accompanies the exhibition with essays by Lowery Sims, Peter Selz, and Robert Storr.[1]

Arnold Mesches: The FBI Files at Kendall Art Gallery at Pat & Martin Fine Center for the Arts exhibits a series of collages resembling illuminated manuscripts. The mixed-media pieces replete with mid-century iconography were transformed from 57 documents from his 760-page dossier, citing 26 years of FBI surveillance.

Arnold Mesches: Minispective at Centre Gallery on Wolfson Campus offers a look into the process and methodology behind many of the artist’s large-scale works produced between 1996-2012. Included are small paintings, drawings, and collages––a roadmap though the experiences and imagined realities of Mesches.

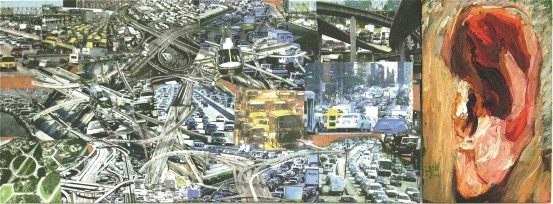

Arnold Mesches, “Noise 5,” 2011, mixed-media collage,

12 x 32 1/4 inches. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Arnold Mesches: Noise at the North Gallery on the North Campus displays over 10 works from 2010 to present. The series reinterprets Brueghel’s Renaissance motifs through present day semiotics where opposite extremes happen simultaneously. Mesches’ allegorical staging shows the complexities of a burgeoning society and the angst of its discord.

Though mostly self-taught, Arnold Mesches attended the Art Center School (now Art Center College of Design) on a 1943 scholarship where he gained formal training in composition from professor Lorser Feitelson. His early aspirations to become a commercial artist segued into painting as an illustrator in Hollywood’s film industry. The oppressive entanglements he faced as an activist in the McCarthy Era during the late 1940s and 1950s––and consequential shadowing by the FBI from 1945 to 1972 revealed a dicey tome of the artist’s political and social activities. This involvement helped shape his view of the cultural discourse and define the socio-political currents of our time.

Mesches was influenced by Brueghel and Goya; German Expressionists Ernst Kirchner, Käthe Kollwitz, and Anselm Kiefer; and Social Realists Ben Shahn, José Clemente Orozco, and the Mexican muralists. His paintings reveal a dissension of government views on issues concerning the working class, economic hardship, war, racial injustice, class structure, and power, much like the works of Post-World War II figurative Abstraction and Expressionists Reg Butler and Leon Golub; German Dadaist/Expressionist George Grosz; and Abstract Expressionists Willem de Kooning and David Smith.

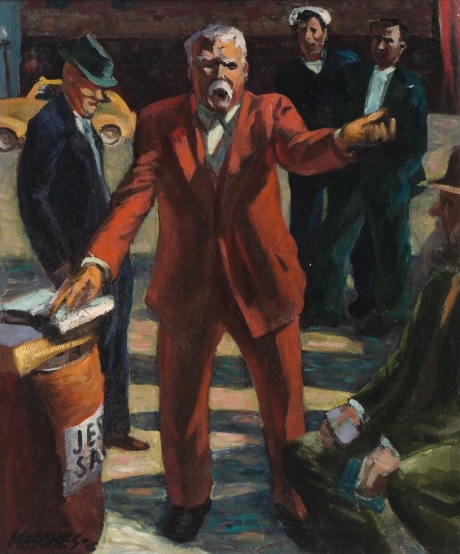

Arnold Mesches, “Anomie 2001: Coney,” 1997, acrylic

on canvas, 80 x 96 inches. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Social commentary is a narrative theme in Mesches’ work. Series such as: Anomie (1989-2006), It’s a Circus (2004-2005), and Coming Attractions (2005-2007) are reminiscent of the theoretical touchstones of Mikhail Bakhtin, who signified carnivalesque humor as a participatory spectacle and social force in cultural transformation; and Bertolt Brecht, whose exploration of epic theatre presented a social and ideological forum for political expression and critical thought.

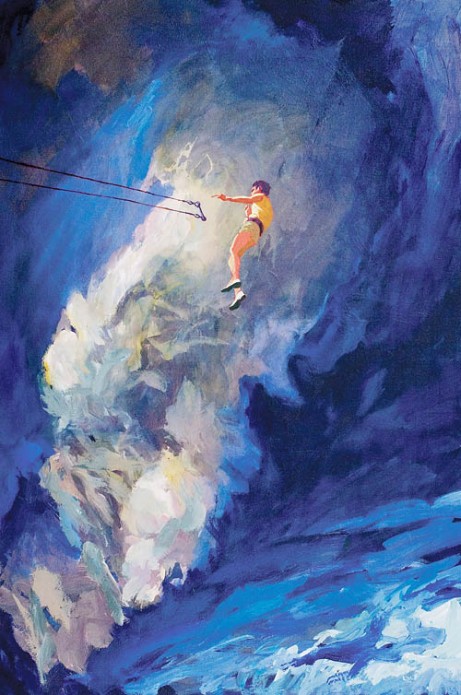

Weather Patterns (2009-2010) is a series about the precariousness of today. The incongruous themes align with Surrealist techniques and imagery, which express a free association of visual elements. This notion exemplifies the psychological theories and dream studies of Sigmund Freud, and the political ideas of Karl Marx.[2] Mesches also explores this construct in Coming Attractions (2005-2007) evocatively illustrating the Bush years and the uncertainties of life.

“Weather Patterns 10” (2009) depicts a trapeze artist in mid-flight alongside an imposing tidal wave. His sunlit physique is clothed in bright yellow, taupe, and orange in sharp contrast to the deep azure blues of the turbulent sea. The acrobat is in static equilibrium on the verge of safety, as a swinging bar beckons his grasp to offer reprieve from a sky fall into the abyss. The powerful juxtaposition alludes to the instability of the day and our futile attempt to control an unpredictable world with an unforeseeable future.

The FBI Files (2000-2003) is a series of interpretive montages from Mesches’ activist years. The censorship in the film industry, which blacklisted artists and writers for alleged communist subversion during the Hollywood strike of 1946-1947 contributed to the national consequences of the McCarthy era in the late 1940s and ‘50s. Mesches gained access to his abridged FBI files in 1999 through the Freedom of Information Act after the demise of The House on Un-American Activities Committee. This inspired an eclectic array of collages from the partially blacked-out documents that reminded him of Franz Kline paintings.

The series, resembling contemporary illuminated manuscripts, was first exhibited in 2003 at The Museum of Modern Art’s PS1 in New York and traveled to other venues including the Skirball Cultural Center, Los Angeles; The Weatherspoon Museum, Greensboro, North Carolina; and the University Galleries at the University of Florida School of Art and Art History, Gainesville, Florida. Peter Selz notes, “The exhibit happened to coincide with the passage of George W. Bush’s odious Patriot Act, which permits broad surveillance of citizens, and remains largely in force in the Obama administration.”[3]

Arnold Mesches, “The FBI Files 56,” 2003, acrylic, Polaroids, and

paper on canvas, 14 x 22 inches. Collection of Glenn and Trish

Zelniker. Photo courtesy of the artist.

“With each new countenance, Mesches alchemizes the Renaissance glazes and vigorous, wild brushstrokes, until his canvases rival Action Painting, the human face barely distinguishable in the gestural paint.” ~Peter Selz _______________________________

“The FBI Files 56” (2003) is a diptych collage incorporating a page from Mesches’ file. On the left is a portrait of a man in a dark suit. His head is shown in close up disproportionately large for his body. A pompous expression is loosely painted in analogous shades of vermillion, red, gray, and black, as swashes of white cast a revealing spotlight on the intent of his message. The subject’s exaggerated features are caricaturistic to that of an orator, a trial prosecutor, or perhaps McCarthy himself.

A Federal Bureau of Investigations letterhead with singed edges is displayed on the right panel mounted close to the diptych’s center. The typed content describes an announcement designed by Mesches entitled “Come Walk With Us For Peace” that urges attendance at a vigil under the auspices of the American Friends Service Committee on Saturday, April 1, 1961. Further down on the document stamped May 31, 1961, the text reads: “A suggested letter to President John F. Kennedy regarding disarmament; and an announcement about the Walk For Peace.”

Mid-century cutout reproductions border the page with objects such as: Roman warriors, keys, dark mannequins dressed in pink and green, two doll heads, one end of a double Ferris wheel, a winged sculpture, a skeletal spine, a tricycle, finger puppets, and a partially-eaten apple. The background transitions from black to vermillion unifying the disparate images in a surrealistic dreamscape of existence.

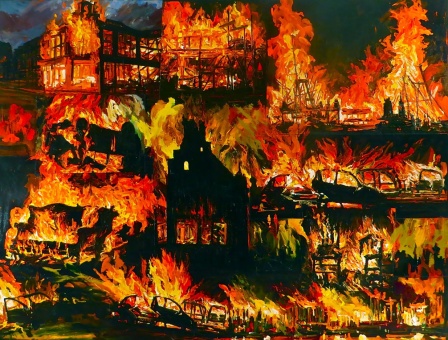

Arnold Mesches, “Shock and Awe 1,” 2011, acrylic on canvas, 44 x 66 1/2 inches,

acrylic on canvas. Photo courtesy of the artist.

The vastness of Arnold Mesches’ oeuvre is astounding. From the sublime beauty of his haunting portraiture and intimate sketches to the profound intensity of his paintings signaling a conviction towards social change, Arnold Mesches: A Life’s Work is a compelling trek into the mind’s eye with an empowering initiative that demands justice for all.

For more on the work of Arnold Mesches, visit:www.arnoldemesches.com.

See: “Participant Observation: A Conversation with Arnold Mesches,” by Jill Thayer, Ph.D., Contributing Writer, ARTDISTRICTS Magazine, Miami.

[1]Arnold Mesches: A Life’s Work is published by Cement House and distributed by the University Press of Florida. Exhibition Catalogue design by Connie Hwang Design, San Francisco, © 2013 Cement House.

[2] “Surrealism,” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, © 2000-2012 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, online. 17 Feb. 2013 <http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/surr/hd_surr.htm>.

[3] Selz, Peter. “Arnold Mesches: Aesthetic and Political Engagement,” Arnold Mesches: A Life’s Work, Gainesville, Cement House, (2013): 6. Exhibition Catalogue.

Arnold Mesches at MDC Galleries of Art + Design

Arnold Mesches: A Life’s Work, February 14 – May 4, 2013, Miami Dade College Museum of Art + Design, 300 NE 2nd Avenue, Miami, FL 33132, 305.237.7700, www.mdcmoad.org

Arnold Mesches: The F.B.I. Files, February 15 – March 22, 2013, Kendall Art Gallery at Pat & Martin Fine Center for the Arts, Kendall Campus – 11011 SW 104th Street, (Bldg. M)

Arnold Mesches: Minispective, February 15 – March 29, 2013, Centre Gallery, Wolfson Campus – 300 NE 2nd Avenue, (Bldg. 1, Third Floor)

Arnold Mesches: Noise, February 15 – March 29, 2013, North Gallery, North Campus – 11380 NW 27th Avenue, (Bldg. 5)

__________

Participant Observation – Interview with Arnold Mesches

Arnold Mesches_Participant Observation by Jill Thayer PhD

“I believe in progress and social change, and things of that kind. I’m a radical progressive.”

BY JILL THAYER, Ph.D.

Born in the Bronx and raised in Buffalo, New York, Arnold Mesches moved to Los Angeles in 1943 to accept a scholarship at the Art Center School. He began his fine art career in 1945 and moved to New York City in later 1984, where he lived for 18 years before moving to his current home in Gainesville, Florida with wife and novelist Jill Ciment. In 2009, the University of Florida awarded Arnold Mesches an Honorary Doctorate. A retrospective commemorating the artist’s 90th birthday opened at Miami Dade College Museum of Art + Design at the Freedom Tower. The exhibition is on view February 14th through May 4, 2013. Arnold Mesches: A Life’s Work features over 225 works spanning from 1945 to 2012 in four campus galleries. This marks the artist’s 136th solo show to date. A 260-page book accompanies the exhibition with essays by Peter Selz and Robert Storr, and an introduction by Lowery Sims. Mesches is represented in major museums and collections throughout the country.

JILL THAYER – You grew up in the Depression. What memories do you have of this time and its impact on your career as an artist?

ARNOLD MESCHES – All kinds of memories. It was a horrible time. It was very difficult. My father could never find work. My uncle tried to do all kinds of things and my father worked with him. Actually, they bought and sold old gold then he finally got a three-day job at Mel’s 9.99 clothing store. It was a very, very, very rough time. I had an uncle in New York who wanted to be a painter and another uncle who was sort of talented. He said, “Why don’t you try a little of this or a little of that.” But nothing really as a child got to me. But, when I showed talent, my uncle, who became a well-known teacher and the head of the high school educational system in the City of New York, suggested I study advertising design because painting and fine art was not the way to make a living.

J.T. – Did you take art classes in high school?

A.M. – I went to Buffalo Technical High School (1937-41) and six out of eight class were design classes. I was one of eight people to receive a state scholarship and mine was to Art Center School in Los Angeles. Art Center had been going for some time. It was a small place on 7th Street in LA. It was a bunch of little cottages, that’s all it was. This was long before the big move to Third and then to Pasadena.

J.T. – Was your family supportive?

A.M. – Yes, as long as I was going to earn a living they were supportive. The minute I decided to become a fine artist, they looked at me like I was stark raving mad.

J.T. – You attended Art Center for a few years as a commercial artist then decided to pursue painting?

A.M. – There was something more to that. My uncle in New York, who always wanted to be a fine artist and never quite made it died at 51 or 52 of a heart attack. I didn’t want to do that. He was an advertising designer at one point and I decided that it would only give me heart attack in my fifties. Beside that, I wanted to say something of my own and not for Ivory Snow or Coca Cola. I wanted to express myself.

J.T. – What did you take away from Art Center?

A.M. – It gave me discipline certainly. That was very important. And, one of the things that happened was they needed a substitute teacher in a drawing class and even though it was a design school, they hired a painter to teach because he was known for his drawings skills. His name was Lorser Feitelson. Lorser used to give lectures in the middle of the class on composition and they would be the only real, honest-to-god fine art background I had––two months of Lorser’s lectures! We became dear friends afterward and I organized a memorial for him when he died at 80. I was instrumental in getting Helen [Lundeberg] and Lorser together.

J.T. – Can you share that story?

A.M. – Lorser was teaching at Art Center and we were friends. One day at lunch, he says, “You know, I have a new girlfriend and I need a place to rendezvous with her. Can I use your apartment?” So I gave him the key to my apartment, which was right around the corner from Art Center, and he and Helen got together.

J.T. – And their marriage lasted many years.

A.M. – Oh, yes, yes. Because, Lorser was floundering around, he couldn’t find a woman. He was seeing a lot of different people, and Helen came along and that was it.

J.T. – Let’s talk about your retrospective, which marks your 90th birthday.

A.M. – The retrospective at the Freedom Towers at Miami Dade College opens in February and my birthday is in August, but the exhibition commemorates it. The earliest painting in the show, “The Plaza Preacher,” was done in Lorser’s class in 1945. Actually, Lorser took it off the easel and helped me buy a frame in my first exhibition at the time.

J.T. – How many works will you have in the show?

A.M. – In the main gallery there will be anywhere from 60 to 85 large paintings ranging from 1945 to 2012 and the other three satellite galleries have drawings and collages, and probably the “FBI Files.”

J.T. – In your early career, you worked for a film studio then Hollywood went on strike. How did the socio-political climate of the time affect you?

A.M. – Well, the Hollywood strike was a big influence on me. I was doing storyboards and set illustrations for a Tarzan movie at the Sol Lesser Studios on the RKO lot. Three months after I started my job, Hollywood went on strike. They broke the Hollywood Unions, which incidentally set the stage for the Hollywood blacklists.

J.T. – The censorship of the industry contributed to the national consequences of what was going on in the McCarthy era.

A.M. – It began the whole McCarthy period. The Cold War had come on and the House on Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) started then. That’s when I began to get shadowed by FBI and the whole country went right wing. McCarthy was running the roost at that time.

J.T. – The HUAC investigated allegations of communist activity beginning in 1945.

A.M. – It’s quite amazing what happened in those years.

J.T. – They had files on you from 1945 to 1972?

A.M. – Yes.

J.T. – What initiated their interest in you?

A.M. – First of all, I did drawings and covers for a left-of-center magazine called “Frontier,” which was like the “Nation” on the West Coast. I made picket signs for every cause, I signed petitions, and I marched for peace––a dirty word in those days, apparently.

J.T. – How did this impact your career?

A.M. – Obviously, everything comes into your veins and pores when you’re an artist. Everything you do. And you try to find ways to express yourself and all your feelings about these things.

J.T. – Did it affect your ability to show or disseminate your work?

A.M. – Yes. There were times when I was blacklisted from shows. I was blacklisted from a job in Salt Lake City. Yes, definitely.

J.T. – Was there a resolve to the files and their interest in you?

A.M. – Yes. Things changed in the country in 1972. The House on Un-American Activities Committee was thrown out of Congress by a much more left-wing, middle of the road, you know, Rooseveltian period.

J.T. – Yes, and funding?

A.M. – Well, the funding was taken away, right. The ‘60s had come into play with the anti-Vietnam War days and things really began to change. So, slowly but surely, the HUAC funding was taken away and that’s when it all ended. It affected hundreds of thousands of people. If you signed a petition against rent control or in favor of rent control, you had a file. I knew all of the blacklisted artists and the writers. I knew the “Hollywood 10”. I did picket signs for when they went to jail and the demonstrations.

J.T. – Tell me about the methodology of your collages in the FBI Files.

A.M. – I was doing historical paintings at the time and wanted to continue with an odd concept of the history of the country. And I thought, what better than the history of my files. When I acquired them, they were just plain beautiful in the way they were blacked out. They looked like Franz Kline’s paintings. I wanted to do what the old illuminated manuscripts did to retain the history of the world so I made them into contemporary illuminated manuscripts. Rob Storr was the curator at MoMA at that time and he came to the studio to see the work. [Mesches adds how Storr explained that MoMA was too conservative, but made a call to Alanna Heiss who sent up Associate Curator Daniel Marzona and he loved the work.] The exhibition at PS1 was supposed to run for two months and there were 500 people a day coming to see the show so they extended it for two more months. Meanwhile, my wife Jill gets a job in Gainesville, Florida and we make plans to move in January. So, I left New York in a way . . . I’m at the Museum of Modern Art’s affiliate, PS1 and I’m leaving New York! After that, I helped align 10 travel venues for the series nationally. There was a lot that went on before PS1, which was many, many years ago.

J.T. – Your work is influenced by many culture contexts, are there other factors?

A.M. – Everything you go through. You live life and life influences your work if you just allow it to. From the beginning with “The Plaza Preacher,” I was always socially conscious or socially orientated in my work. I did several series including one on the Holocaust, and another called “The Masquerade Series,” which was about the madness of our times. Euripedes said, “Whom the gods would destroy, he would first make mad.”

J.T. – In the series, It’s a Circus, your themes remind me of Mikhail Bakhtin’s theory, “carnivalesque.” [1] The participatory spectacle is a social force in cultural transformation.What drew you to the medium and genre you are working in now?

A.M. – I gave up oil in 1966 and now I am painting in acrylic. The entire FBI Series is mixed media, I do a lot of collages, I have done over 300. I layer things. When you talk about methodology, I layer paint. I go from the beginning and always start on a colored ground. I do not work on a white gesso. I always work on a colored ground. I apply my acrylics the same way I applied my oils in the sense that I know the chemistry of paint, and I only use acrylic that has the same chemistry as the oil paint. There are only two companies that do that. Paint has chemistry. Some earth colors are opaque and other colors are transparent by their chemistry. When I paint, my layering has to do with opaque and transparency.

J.T. – What about your thought process?

AM: I have been working in series for a long time so it’s not just a question of how do I work on one painting. It makes all kind of happenstance. I see images and they begin to work on me. I start making sketches and drawings, letting things happen and putting things together, and looking at things together. I don’t sit there and say, “I’m going to do a painting about this or this.” I allow it to kind of grow. One thing grows out of another. Each series has grown out of the other.

J.T. – Do you have a belief system that informs your life or work?

A.M. – Yes. I believe in progress and social change, and things of that kind. I’m a radical progressive.

J.T. – Thank you Arnold, for your contributions to the cultural discourse.

For more on the work of Arnold Mesches, visit: http://www.arnoldemesches.com.

“Arnold Mesches: A Life’s Work”

Miami Dade College Museum of Art + Design

at the Freedom Tower

February 14 – May 4, 2013

600 Biscayne Boulevard

Miami, Florida 33132

(305) 237-7700

[1]“Carnivalesque” refers to a literary mode that subverts and liberates the assumptions of the dominant style or atmosphere through humor and chaos.

Pingback: The Artist Who Captured America's Most Dramatic Courtroom Moments—And Was Hounded by the FBI | CrimeReads

Thanks for sharing this article on the many layers and cultural contributions of Arnold Mesches’ extraordinary career.